Sundial to return to Capitol Campus for another January dedication

Linda Kent

(360) 972-6413

linda.kent@des.wa.gov

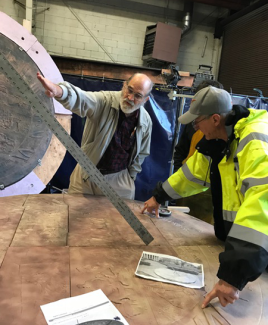

Larry Tate, Principal at Fabrication Specialties Ltd., and University of Washington Astronomy Professor Woody Sullivan consult on the necessary angle and placement of a new gnomon to ensure time-keeping accuracy. Both have key roles in renewing the sundial.

Six months after the iconic Territorial Sundial between the Legislative Building and the Joel Pritchard Library was removed for restoration, it will come home for another January dedication.

Following its first overhaul in 59 years, the sundial will be sturdier than ever and maintain its original appearance. Once work is complete in early January 2018, a dedication event will be scheduled. The sundial was originally dedicated in January 1959.

The state's project goals for the sundial's renewal include:

- Retaining the original artwork and aesthetics.

- Accuracy in reading solar time.

- A strengthened form to improve durability and deter vandalism. For example, the original copper of the sundial face was only 1.2 millimeters -- less than the thickness of the standard copper penny. The updated sundial will be about 9.5 millimeters – about the thickness of four half-dollars stacked together.

The sundial was designed by artist and master craftsman John W. Elliott (1883-1971). It has eight panels depicting scenes from Washington's territorial history, from Capt. Vancouver's exploration of Puget Sound to the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad.

Seattle art contractor Fabrication Specialties, Ltd. used the original sundial as the pattern to mold and re-cast the dial's artwork in bronze, and has designed a sturdier gnomon that closely follows the original design. Due to the sundial's size – approximately 6 feet in diameter – a single casting would be extremely difficult and expensive. Thus, it was done in eight sections using a traditional sand-casting process.

Fabrication Specialties welded the eight cast sections together. Following that, approximately 18 feet of 2-inch wide bronze facing was welded to the outer edge of the dial. A labor-intensive processes of smoothing out the joints where welding occurred – called chasing – is now underway to make joints virtually invisible. The sundial will be finished with a chemical patina, sculpted areas will be lightly burnished to highlight the embossed details, and a protective wax coating will be applied to seal and stabilize the surface.

Preserving artwork into the future

Enterprise Services consulted with both the Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation and the State Arts Commission in deciding to replicate the original artwork. University of Washington astronomy professor and sundial expert Woody Sullivan is consulting on the project to ensure the finished sundial's accuracy.

"It was difficult to let go of the notion that we could strengthen and repair the original artwork, but we had to recognize and accept its material fragility. We don't want to be faced with this same repair problem only five or 10 years from now," said Marygrace Goddu, Enterprise Services cultural resources manager.

Gov. Jay Inslee said it's important to preserve campus artwork into the future.

"The sundial is just one example of the meticulous care and effort that go into preserving the many important works of art and memorials on our beautiful Capitol Campus," Inslee said. "It is crucial to preserve these works for both current and future generations, and I am pleased that the sundial is ready to keep time for the first time in decades."

Timekeeping

The sundial was removed for work in July. Its gnomon — the part that casts a shadow — and the well-weathered copper face of the dial were each in considerable need of repair.

Sullivan said simply cleaning and repairing the original sundial would have been unlikely to produce an accurate time piece.

"The original thin copper material on the face is subject to slight wrinkling and movement over time, which while not very visible would throw off the sundial's accuracy," he said. "A thicker, completely level, and more durable surface is needed – not to mention a sturdier gnomon -- to preserve its time-keeping abilities into the future."

Early photographs show that the original gnomon was bent soon after the sundial's installation. It suffered repeated damage from vandals and curious passersby over many years.

Its high-copper alloy, light-gauge material, and weak attachment made the gnomon pliable and especially vulnerable to mishandling. In addition, water seeping in through the center seam of the sundial's face corroded the underlayment the dial was mounted atop. As an initial stabilizing measure, the underlayment was replaced in 2008 and temporary alterations to the gnomon were made.

The 2017-18 repairs will complete the long-needed work on the sundial. The project will be paid for with operating funds designated within the Public and Historic Facilities fund for care of campus memorials and artwork.

After sections are cast, the next step is welding them together.

Traditional sand casting process

The traditional sand casting process creates a two-part casting "flask" used to contain the molding sand. The flask has a top half, called a "cope" and a bottom, called the "drag."

For the sundial, flasks were custom-built of wood and fitted to each of the eight sections that needed to be cast. The flask initially works like a dam to hold the sand.

After the drag is filled with sand, it is compressed to take the form of the artwork, then flipped over. Sand is then compressed into the "cope" or upper portion of the flask.The original artwork is carefully removed, leaving behind an exact impression in the sand.

A passageway or "gate" into the void is added to the mold for the molten bronze to flow through. Molten bronze is then poured through the gate into the flask, which now houses the mold, like a shell.

Once all eight sections of the sundial were cast this way in bronze, the sections were carefully trimmed to fit the pieces together along pre-determined seams, and welded together front and back.

About the artist

Territorial Sundial artist John W. Elliott (1883-1971) was a master craftsman and architectural sculptor whose public art projects across the Pacific Northwest included a gilded eagle for the front of the Olympia Armory, 34 repousse panels in the Seattle City Light Building, and the sculpted heads of lawgivers on Condon Hall at the University of Washington.

The original Territorial Sundial at the Capitol Campus was one of several significant art installations commissioned by State Librarian Maryan Reynolds and architect Paul Thiry with the construction of the Washington State Library building.

Elliott was born in Sheffield, England, the son of a stonecarver. He was trained as a silversmith and immigrated to the United States in 1906, settling first in New England. Elliott moved to Seattle in 1924 and became a leading member of the Seattle arts community. From his studio in West Seattle, he created renowned sculptures and metalwork for buildings across Washington, Oregon and British Columbia, according to the University of Washington Libraries Special Collections.

Elliott was a founder of the Craftsman’s Guild of Washington, which was formed in 1938 to recognize skilled artisanship across numerous disciplines. He also served as a member of the Seattle City Art exhibition committee and a district supervisor for the State Board of Vocational Rehabilitation.

Sign up to receive Capitol Campus Updates via email or text message.

Follow Enterprise Services on Twitter.

Learn more about Visitor Services on Facebook.